Introduction and Brief History

The word Ukiyo-e literally translates to ‘pictures of the Floating World’. It was called so because at the time this art flourished, Edo (modern Tokyo) was the center of military dictatorship that brought about fast economic growth, which benefited the merchant class. The affluent merchant community indulged in rich entertainments such as kabuki theatre, courtesans, geisha etc. and such a hedonistic lifestyle came to be known as Ukiyo (floating world). Japanese artists of that time created woodblock prints on such themes of dance, art , history, theatre and a full-fledged Japanese art genre Ukiyo-e evolved by the late 17th century.

Starting with monochromatic Japanese Prints pioneered by Hishikawa Moronob in the 1670’s, Ukiyo-e Japanese Woodblock Print art advanced first to prints with certain colored areas and then by the 1760’s to production of vibrantly colored Japanese Woodblock Prints that employed multiple woodblocks.

By the late 18th century a thriving fraternity of master Japanese Woodblock Print artists had come about comprising of renowned artists such as Kiyonaga, Utamaro, Sharaku and others.

A pair of noted master artists, Hokusai and Hiroshige came about in the 19th century who were best known for their landscape woodblock prints. Hokusai’s Great Wave off Kanagawa and Hiroshige’s The Fifty-three Stations of the Tokaido are among the best-noted works among Japanese Woodblock Prints of the Ukiyo-e genre.

It is to be noted that while some Ukiyo-e artists were painters, most of the works from this Japanese art genre are Woodblock Prints.

However with the advent of Meiji Restoration (a revolution in Japan in the 19th century) that brought about technological and social modernization and with deaths of senior master artists, particularly Hokusai and Hiroshige, Ukiyo-e woodblock print production went down steeply.

Since this art largely flourished during 17th through 19th centuries, the Japanese Woodblock Prints available for sale today are all antiques.

Transformation of Ukiyo-e from Paintings to Woodblock Prints

It was Hishikawa Moronobu, a Japanese artist-illustrator who lived from 1618 – 1694, who produced the first Ukiyo-e Japanese Woodblock Prints to meet the increasing demand for Ukiyo-e Japanese art.

Moronobu was hugely successful in his endeavor and went on to develop a unique style portraying female beauties. He also began producing illustrations not just for books but also as single-sheet images that could be solo or a part of a series of sheets portraying a complex scene or event.

When Hishikawa’s school of art style attracted a big following and also imitators, a new art form of Ukiyo-e Japanese Woodblock Prints was born.

Evolution of Color and Complexity in Ukiyo-e Japanese Woodblock Prints

There was a natural demand for color in monochromatic prints

and initially these were colored externally for special commissions. Prints in

early 18 century were hand-tinted orange or occasionally green or yellow.

There was also a vogue for pink-tinted prints and

lacquer-like effects with ink subsequently but it was in 1744 that first

successes were achieved in color printing with multiple woodblocks, one for

each color. Though earliest colors were beni pink and vegetable green but a

method was now in place for introduction of complex color shades in prints.

In the late 18th century Ukiyo-e reached a peak with

full-color prints. These were brilliantly colored and called Nishiki-e meaning

‘brocade pictures’. These Japanese Woodblock Prints first emerged as expensive

calendar prints for sale printed with multiple woodblocks on very fine paper

with thick, opaque inks. The woodblocks for these Japanese prints were later

re-used for mass Japanese Woodblock Prints available for sale.

Suzuki Harunobu (1725-1770) was the first to layout

delicate, romantic Japanese Woodblock Prints that realized the expressive and

complex color designs. These Japanese woodblock prints were printed with up to

a dozen separate blocks to handle color and half-tone variety. These colored

woodblock prints were a dominant style 1765 onwards and caused a steep decline

in demand for other styles with limited palettes of Benizuri-e and Urushi-e,

alongwith hand-colored prints.

Following Harunobu’s death in 1770 Ukiyo-e Japanese

Woodblock Printing art expanded with artists like Katsukawa Shunsho producing

high fidelity portraits such as those of Kabuki actors and collaborators such

as Koryusai and Kitao Shigemasa who largely depicted women and contemporary

urban fashions celebrating real-world courtesans and geisha.

Around the same period, i.e. 1770s, Utagawa Toyoharu

introduced Western perspective techniques in Ukiyo-e Japanese Woodblock Prints

enabling inclusion of landscapes among Ukiyo-e subjects. By 19th century these

techniques were assimilated in Japanese woodblock printing art enabling

renowned Japanese print artists such as Hokusai and Hiroshige to include highly

refined landscapes in their Japanese prints later on.

The Peak Period of Ukiyo-e Japanese Art

Ukiyo-e Japanese Woodblock Prints as an art reached its peak

in late 18th century and then suffered sharply under tensions of reforms of

Meiji Restoration in the 19th century.

The 1780s for example, scenes of traditional Ukiyo-e

Japanese Art subjects like beauties, realistic style kabuki actors including

musician and chorus, and urban set ups emerged on large sheets of paper, often

as multiprint horizontal diptychs or triptychs, depicted by the artist Torii

Kiyonaga.

Another Japanese artist, Utamaro was popular in 1790s for

portraits of beautiful women that focused on the head and upper torso. He

experimented extensively with line, color, printing techniques to highlight

subtle differences in subjects from a wide variety of class and background in

terms of their features, expressions, and backdrops.

An accomplished Japanese artist Sharaku emerged in 1794 for

a short period of ten months in 1794. Within this short span of career he

produced striking portraits of Kabuki actors. His prints were realistic in that

they emphasized differences in the actor and the character portrayed. His

prints depicting expressive, contorted faces were in contrast to those of

Harunobu or Utamaro, Kabuki characters in whose prints had serene, mask-like

faces. Sharaku’s work ceased mysteriously and his identity is still unknown.

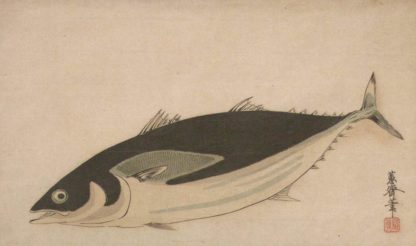

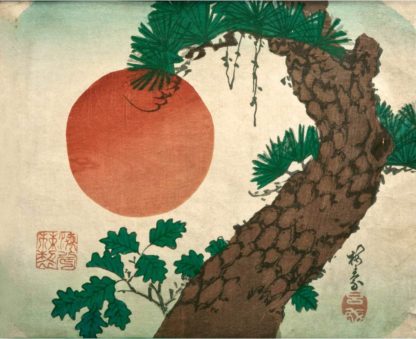

Introduction of Landscape, Flora and Fauna in Ukiyo-e Japanese Prints

Landscape and Nature prints emerged during Tenpo Reforms in

19th century when outward displays of luxury, affluence and even depiction of

actors and courtesans were suppressed.

Ukiyo-e artists then shifted their focus on producing

Japanese Woodblock Prints with landscapes, nature, travel scenes, birds and

flowers as subjects. So far these subjects were given limited attention, even

though these formed an important element in the works of Kiyonaga and Shuncho.

However by the late Edo period landscape developed as a genre of its own,

particularly through works of Hokusai and Hiroshige. Japanese landscape prints

differed from their western counterparts in that these relied heavily on

imagination, creativity and atmosphere rather than strict adherence to nature.

Hokusai, self-proclaimed as ‘mad painter’ created work

focused on formalism influenced by Western art besides the lack of

sentimentality that is common to Ukiyo-e Japanese Prints in general. He created

much illustrious work including the famous Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji that

also includedhis best-known Japanese print and one of the most famous works of

Japanese woodblock print art – The Great Wave off Kanagawa. Thirty-six Views of

Mount Fuji was instrumental to popularization of landscape genre in the art of

Japanese woodblock printing. Subsequently other established Japanese woodblock

print masters such as Eisen, Kuniyoshi and Kunisada followed Hokusai in 1830s

to produce striking landscape woodblock prints with bold compositions.

Hiroshige (1797 – 1858) who specialized in prints of birds, flowers

and serene landscapes and is best known for his travel series Japanese prints

such as The Fifty-three Stations of the Tokaido and Sixty-nine Stations of the

Kiso Kaido, came to be known as Hokusai’s greatest rival.

Hiroshige’s legacy of art continued through his followers,

Hiroshige II, his adopted son and Hiroshige III, son-in-law.